Shilu Manandhar, GPJ Nepal

A veteran political reporter in Kathmandu, Ram Krishna Adhikari had his salary cut in half at the height of the pandemic.

KATHMANDU, NEPAL — The note on the newsroom notice board was short and direct: Employees, go home. At first, Ram Krishna Adhikari wasn’t worried. It was March 2020, and the coronavirus was starting its trek around the globe. To Adhikari, a political reporter at the Annapurna Post, a daily newspaper in the nation’s capital, working from home was a sensible precaution, one that required him to change his routines, but didn’t portend anything worse professionally. But within a month, his boss pulled him aside with bad news: The paper was cutting his salary in half.

Adhikari’s plight was one repeated around the world, as the pandemic gutted commerce and, by extension, media revenue, even as readership surged and access to quality information became a literal matter of life and death. In Nepal, where outlets subsist almost entirely on advertising, about a quarter shut down entirely. More than 1 in 3 print, television and radio journalists lost their jobs, according to a report by Freedom Forum, a nongovernmental organization that advocates for press access. Many who remained faced pay cuts. These days, the industry has stabilized somewhat, but like a patient walloped by illness, it is smaller and less robust.

It’s difficult to quantify what is lost when media outlets shrivel or shut down: What scandals stay hidden? What corruption goes unexposed? In Nepal, the stakes are even higher: The cuts undermined the vibrant media environment that flourished after the country’s decadelong civil war ended in 2006. “The independent media’s presence and outreach has shrunk, and its watchdog role weakened, creating space for the state-controlled media,” the Freedom Forum report says. That presents a significant challenge to the young democracy. “Democracy’s trust is in transparency,” says Lekhanath Pandey, an assistant professor of journalism at Nepal’s Tribhuvan University. “If the media cannot access information, then democracy will be compromised.”

***

Adhikari is 37, and over the course of his life, Nepalese media has whipsawed from predominantly state-run to an array of voices and political perspectives. In 1990, a decadeslong autocratic regime fell, giving way to a constitution that guaranteed press freedom and spurred the growth of independent media. As a young man, Adhikari considered becoming a lawyer, but an acquaintance suggested journalism instead. Good idea, he thought: The profession seemed like a vehicle to meet new people and avoid a 9-to-5 grind. But the civil war, which started in the mid-1990s, threatened his chosen industry’s progress: Dozens of journalists were killed or disappeared, while hundreds more fled the profession. Adhikari himself was detained by the army for nine days. Nevertheless, Nepalese media rebuilt itself post-conflict; before the pandemic, two-thirds of outlets were independent.

Adhikari worked at various daily papers, mainly covering politics, before joining the Annapurna Post, one of the country’s leading Nepali-language publications. In 2019, he was the first journalist to interview the leader of the Communist Party of Nepal, Netra Bikram Chand, after the government outlawed the party — a big enough scoop that a sister paper translated it into English so it could reach a wider audience. When lockdown began, he was deputy bureau chief of the paper’s roughly eight-person political bureau, churning out daily stories as well as larger analysis pieces.

Like most Nepalese outlets, the Annapurna Post relied heavily on advertising from the likes of car companies, banks and the government. With the country’s economy sputtering, ad sales plummeted across all media, but print outlets were the hardest hit, losing 80% of revenue, according to the Advertising Association of Nepal. Most outlets slashed jobs, if they didn’t close entirely. Less than a quarter of media houses kept their entire staff, the Federation of Nepali Journalists says, and no aid program existed to help the jobless journalists financially. The Annapurna Post didn’t initially lay off reporters, but the paper, which once printed 16 to 20 pages a day, shrank to eight, slashing space for finance, opinion, sports and arts coverage. “Besides health, other stories were hardly covered,” says Akhanda Bhandari, the paper’s editor-in-chief.

***

As the coronavirus pinged around the globe, so did rumors on social media: In Nepal, many hospital deaths were blamed — often falsely — on COVID-19. Taranath Dahal watched the misinformation spread on Facebook with dismay, but also resignation. The executive chief of Freedom Forum, Dahal knew the depleted press corps could barely cover daily virus updates, let alone debunk conspiracies. “Journalists could not investigate in the field, and verifying information was difficult,” he says. And they were no match for the volume of dreck. According to a report by International Media Support, a nonprofit based in Denmark, one analysis of 200 million social media posts worldwide related to the virus found about 40% were “unreliable.”

Nepalese journalism is usually a face-to-face endeavor, but amid a lockdown so strict that even grocery shopping was regulated, government, university and nonprofit offices were closed. Trying to chase down sources by phone or email proved exceedingly tough. Adhikari continued reporting from home on the prime minister’s handling of the pandemic, for instance, but he could rarely do the interviews his longer pieces required, so he stopped writing them. As a whole, Dahal says, Nepalese media struggled to cover government misconduct, health care system lapses and the hardships of communities that lacked access to medical care. “There was no proper public discourse,” says Pandey, the Tribhuvan University assistant professor. “Corruption was at its peak while purchasing PPE [personal protective equipment] and vaccines. Media could not do its duty as a watchdog.”

To be sure, these criticisms are mostly speculative. But studies in the United States, where media closures were common even before the pandemic, show a significant link between the vitality of the press and that of democracy. In places where news coverage withered, so did voter turnout, political knowledge and membership in civic organizations. In both the U.S. and Japan, communities with a diminished press spent more on public works projects, suggesting a lack of accountability. “When an independent media fails there’s no public agency to hold state mechanisms to account,” the Freedom Forum report says, “more so in a third world country like Nepal, where corruption is rife and irregularities are ‘order of the day.’”

Yam Bam, 29, covered finance, the environment and current affairs for a weekly magazine in Kathmandu. (He asked that the publication not be named for fear of hurting his future job prospects.) After the magazine shuttered in 2020, he got a tip about possible government misdeeds related to the procurement of COVID-19 vaccines. “It was difficult to verify information and cross-check government information. It was difficult to report on other important issues like corruption due to restriction in movement,” he says. He also wasn’t sure where he could publish the story. He let the tip go.

***

For more than a year, Adhikari’s bosses assured him that the Annapurna Post would restore his pay. That never happened. Bhandari, the editor, says that, to his knowledge, pay cuts across the newsroom were necessary to keep the company open. Adhikari and his wife, who works in insurance, drained their savings and borrowed money from family and friends to support themselves and their young daughter. “We couldn’t compromise on basic necessities like food and rent,” he says. The paper eventually asked employees to resign, so Adhikari and 27 co-workers wrote a public resignation letter demanding back pay. After seven months, and with help from the Federation of Nepali Journalists, they got it.

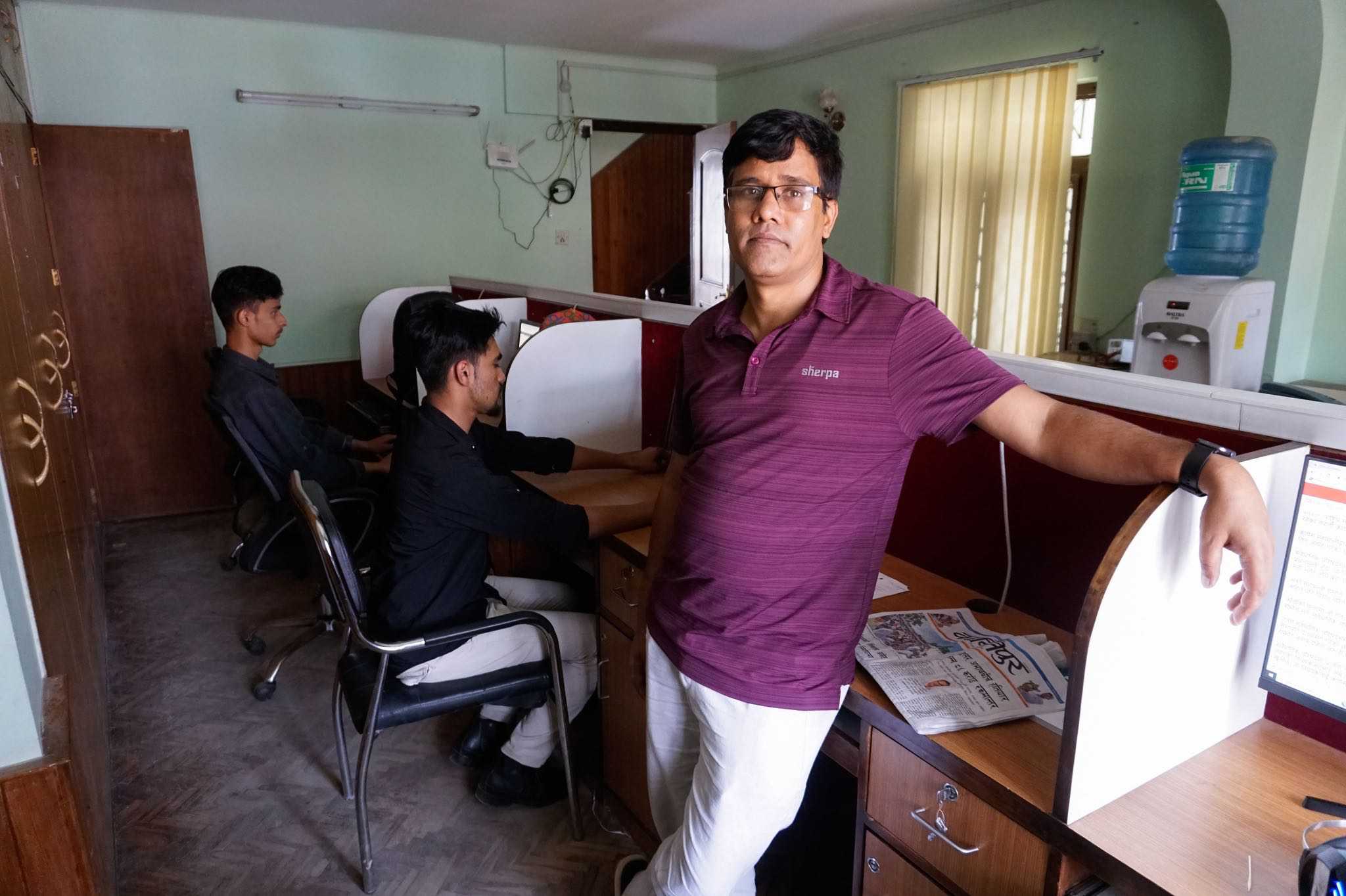

Nearly three years have passed since the day the Annapurna Post sent employees home. “Now media is on track,” Bhandari says. “It is walking, but not running.” The paper is a prime example: still printing, but with about 40 editorial employees instead of 65. Industrywide, Adhikari has noticed ads migrating from print to websites and social media, which, in the U.S., has meant less revenue for outlets and fewer journalism jobs. “I am unsure about the future of media. But I have confidence in myself, and I know I will always find work, no matter how big or small,” he says. Despite the pandemic tumult, Adhikari made out well. In 2021, he co-founded Mero News, a website based in the capital. Eleven reporters cover politics and the economy; Adhikari has his own office with a large desk and minimal clutter. As an editor, he even makes slightly more money than before — though with a newfound awareness of how fleeting that paycheck may be.

Shilu Manandhar is a Global Press Journal reporter based in Kathmandu, Nepal.